See the previous chapter…

- Course overview: goals and introduction

- Positions: latitude, longitude, nautical mile, scale, knots

- Nautical chart: coordinates, positions, courses, chart symbols, projections

- Compass: variation, deviation, true • magnetic • compass courses

- Plotting and piloting: LOPs, (running) fix, dead reckoning, leeway, CTS, CTW, COG

- Advanced piloting: double angle on the bow • four point • special angle fix, distance of horizon, dipping range, vertical sextant angle, radians, estimation of distances

- Astronomical origin of tides: diurnal, semi-diurnal, sysygy, spring, neap, axial tilt Earth, apsidal • nodal precession, declination Moon and Sun, elliptical orbits, lunar nodes

- Tides: tidal height prediction, chart datums, tidal curves, secondary ports

- Tidal streams and currents: diamonds, Course to Steer, Estimated Position

- Aids to navigation: buoys, leading lights, ranges, characteristics, visibility

- Lights and shapes: vessels sailing, anchoring, towing, fishing, NUC, RAM, dredging

3 – Compass navigation

Marine compass

In China [Smith museum] compasses have been in use since the Han dynasty (2nd century BCE to 2nd century CE) during which they were referred to as “south-pointers”. Even though, at first these magnets were only employed for geomancy much like Feng Shui.

Eventually, during the Sung dynasty (1000 CE) many trading ships were then able to sail as far as Saudi Arabia applying compasses for actual marine navigation. As a direct result, between 1405 and 1433, Emperor Chu Ti's Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne ruled the entire South Pacific and the Indian Ocean; a territory that ranges from Korea and Japan to the eastern coast of Africa.

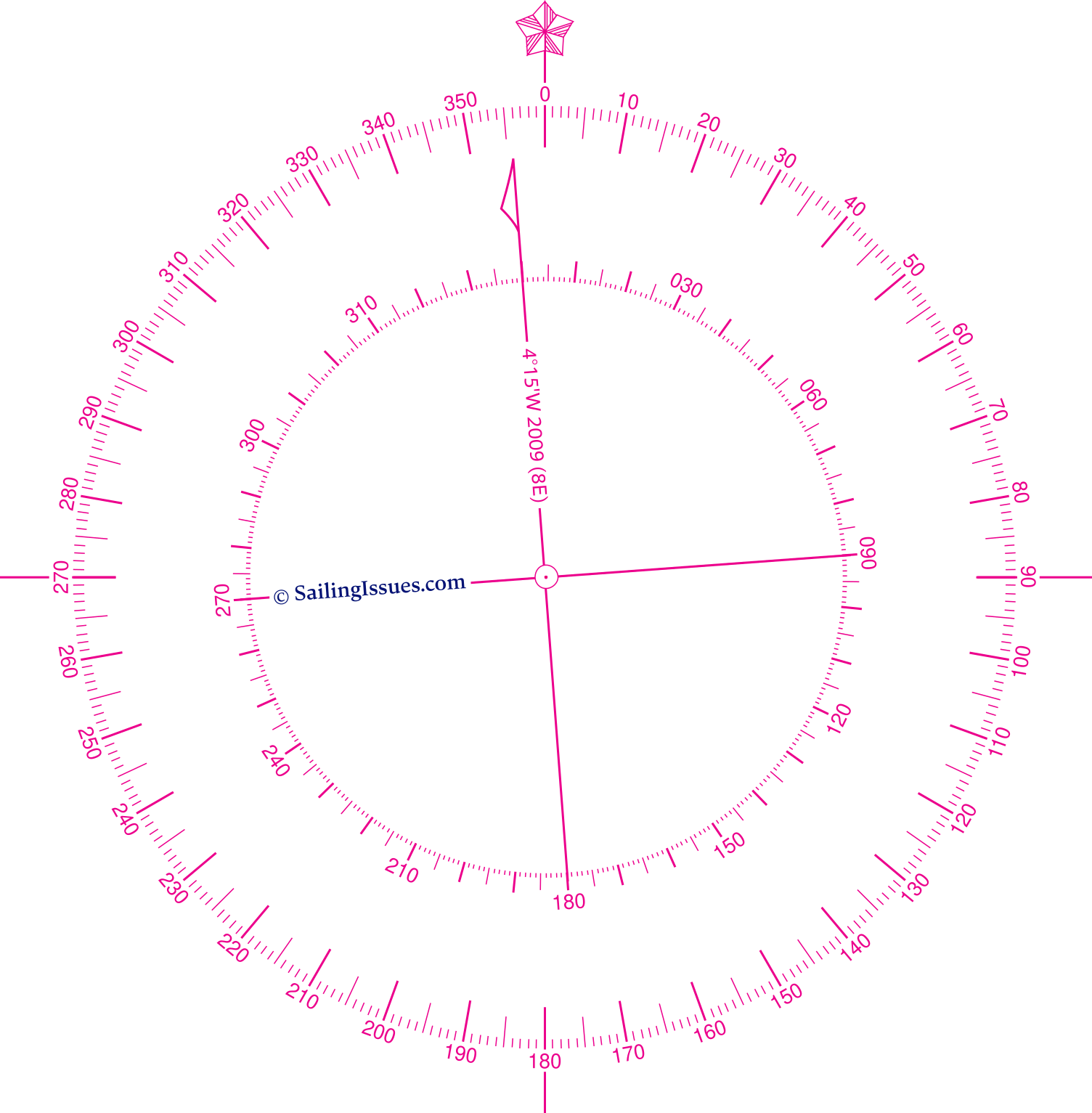

The magnetic variation is shown by the rotation of the inner rose and declared along the arrow: 4° 15' W 2009 (8' E). Find out what this means.

At this time Western mariners were still rather incognizant of the navigational application of the magnet. The first treatise on the magnet itself was written by Petrus Peregrinus de Maricourt : “De Magnete” (1269). Despite that its nautical use was already mentioned in 1187 by the English monk Alexander Neckham, the use onboard only came about around the 13th and 14th century in the Mediterranean Sea.

In 1545 Pedro de Medina (Sevilla 1493-1567) wrote the Spanish standard work “Arte de Navegar” on marine compass navigation. This masterpiece was first translated in Dutch (1580) and was – O Irony – put into practice by Jacob van Heemskerk while the Dutch destroyed the Spanish fleet near Gibraltar in 1607. A drawback, obviously, was Van Heemskerk's own death during this victory.

Magnetic variation

In the fin-de-siècle of the 16th century mariners believed that the magnetic north pole coincided with the geographic north pole. Any suggestion otherwise had been denied by Pedro de Medina.

Magnetic observations made by explorers in subsequent decades showed nonetheless that these dissident suggestions were true.

But it took until the early nineteenth century, to pinpoint the magnetic north pole somewhere in Arctic Canada (78° N 104° W). From then on the angle between the true north and the magnetic north could be precisely corrected for. This correction angle is called magnetic variation or magnetic declination.

2011 3° 59' W

2012 3° 51' W

2013 3° 43' W

2014 3° 35' W

2015 3° 27' W

2016 3° 19' W

2017 3° 11' W

2018 3° 03' W

2019 2° 55' W

2020 2° 47' W

2021 2° 39' W

2022 2° 31' W

2023 2° 23' W

2024 2° 15' W

2025 2° 07' W

2026 2° 01' W

The Earth's magnetic field is produced by electrical currents that originate in the hot, liquid, outer core of the rotating Earth. The flow of electric currents in this core is continually changing, so the magnetic field produced by those currents also changes. This means that at the surface of the Earth, both the strength and direction of the magnetic field will vary over the years. This gradual change is called the secular variation of the magnetic field. Therefore, the encountered magnetic variation not only changes with location, but also varies over time.

The correction for magnetic variation for your location is shown on the nearest nautical chart's compass rosenautical chart's compass rose. In this example we find a variation of 4° 15' W in 2009, with an indicated annual correction of 0° 08' E. Hence, in 2011 this variation is estimated to be 3° 59' (almost 4° west), and for 2020 the estimate is 2° 47' W.

This means that if we sail 90° on the chart i.e. the “true course”, the compass – for the moment ignoring all other compass errors – would read 94° in 2009, and almost 93° in 2020 (and e.g. 92° in 2026, see the list on the right).

Note that the “true course” is often shown as COG “Course over Ground” or CMG “Course Made Good” on your GPS plotter.

Another example: we find from the compass rose on the nautical chart a variation of 2° 50' E in 2022, with a correction of 0° 04' E per year. In 2024 this variation is estimated to be 2° 58', nearly 3° east; if we sail 90° on the chart, the steering compass would read 87°.

A paper or digitized nautical chart can feature multiple compass roses: use the nearest one to obtain the magnetic variation.

Correcting for variation

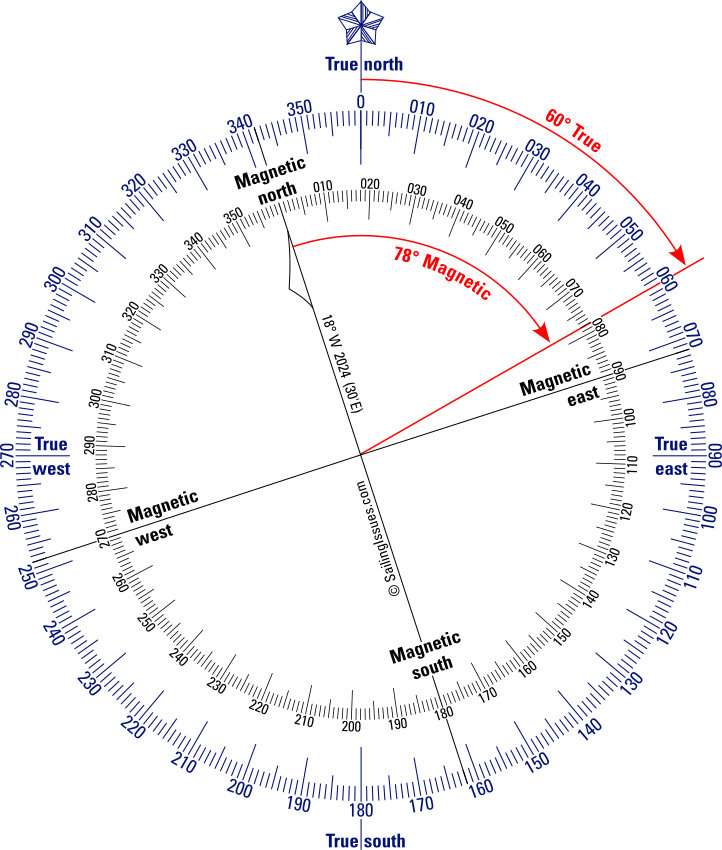

The overlayed compass roses in figure 3.2 illustrate the difference between true north and magnetic north, in this example with a magnetic variation aka var of 18° west.

From the image we find: tc = mc + var

in which mc and tc stand for “magnetic course” and “true course”, respectively.

The inner compass is rotated to the magnetic north with a magnetic variation for 2024 for this location of 18° West or −18°.

The red arrows demonstrate that a true course of 60° corresponds with a magnetic course of 78°, the relation is the magnetic variation of −18°: tc = mc + var.

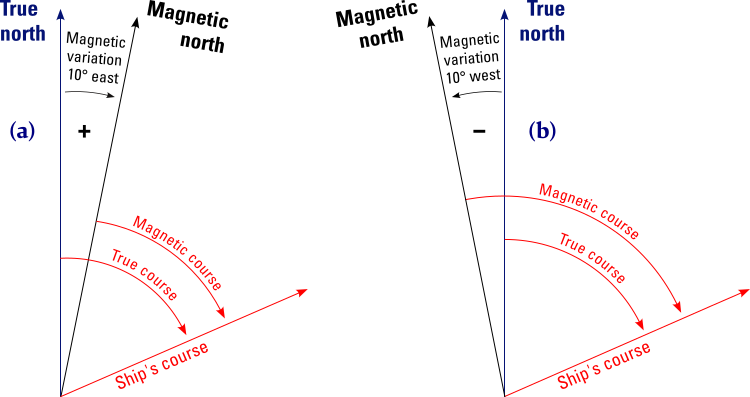

We only need to assign a “minus” for east variation and “plus” sign for west variation, in order to work with just a single equation.

(a) Magnetic variation is east: mc = tc − +var; magnetic course smaller degree angle than true course.

(b) Magnetic variation is west: mc = tc − −var; magnetic course greater degree angle than true course.

All-in-one equation: mc = tc − var or rewritten tc = mc + var .

Conversions from true to magnetic courses

On the chart, the navigator plots the tracks of the yacht in degrees true.

The helmsperson, on the other hand, needs a direction in degrees magnetic to steer our yacht by the magnetic compass.

To convert a true course into a magnetic course we need first assign a “ − ” to a western and a “ + ” to an eastern variation. Note that this makes sense because of the clockwise ↻ direction of the compass rose.

As we see in figure 3.2, the inner circle is turned 18° anticlockwise, hence −18°.

Now, use the same but re-written equation:

mc = tc − var

78° = 60 − (−18°), and also notice the equivalence of +342° clockwise: mc = 60° − (+342°) = −282° and + 360° = 78°.

Meaning: to sail a true course of 60°, the helmsperson has to steer a magnetic course of 78°.

Conversions from magnetic to true courses

The navigator takes bearings from landmarks with a compass in degrees magnetic, and these need to be converted into degrees true to plot the lines of position LOPLOPs on the chart and determine where our vessel is.

To convert a magnetic course into a true course we can use the original equation tc = mc + var. Let's assume that we steered a magnetic course of 200° with a variation of 3° east, then we have to plot a true course of 203°; tc = mc + var = 200° + (+3°) = 203°, or rather with a variation of 10° west, then we sailed a true course of 190°; tc = mc + var = 200° + (−10°) = 190°.

Compass course

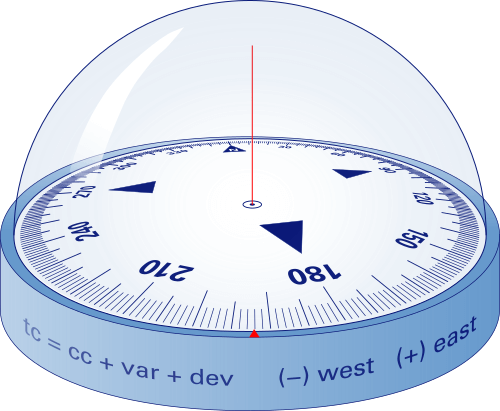

Variation is actually not the only compass error to consider, and

the helmsperson will ultimately need a compass course, i.e. the true course corrected for all compass errors.

For mariners there is also a second commonly correctable compass error, magnetic deviation, that needs to be corrected.

tc = cc + var + dev, where cc stands for compass course, is our ultimate equation for converting true courses into compass courses and vice versa.

And we can replace var + dev = by “total compass error”.

tc = cc + total_compass_error

If the deviation error is zero or irrelevant, then cc gives the same course as mc.

Magnetic deviation

Magnetic deviation – this time a compass error originating from within the ship – is caused by magnetic forces brought on by pieces of metal, such as an engine or an anchor. Moreover, cockpit plotters and other electric equipment or wiring – if too close to the compass – can also introduce a compass error.

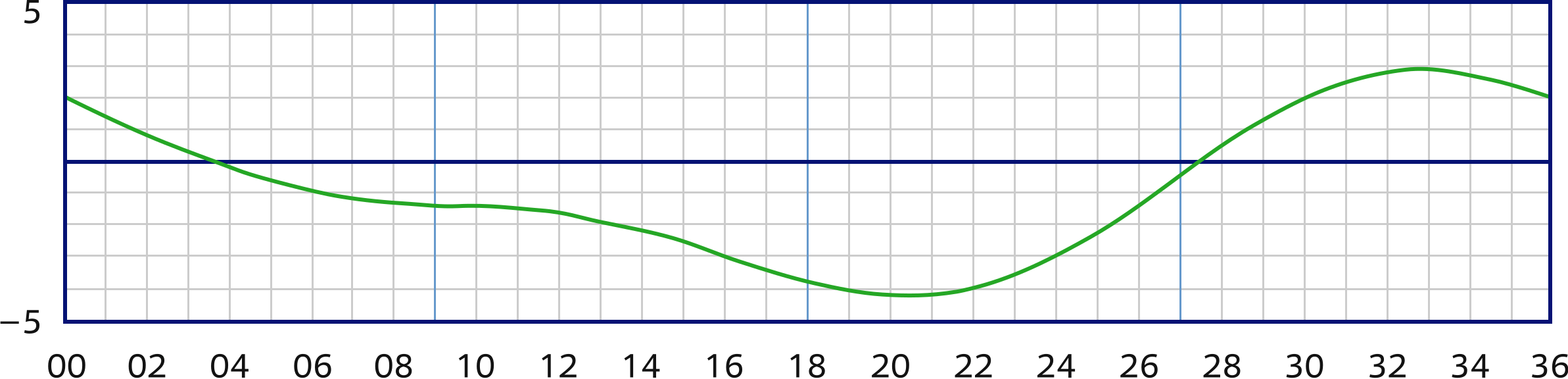

Pertinently, the deviation varies with the ship's heading (HDG), the angle of the yacht's centre line with the true north, resulting in a deviation table / chart as shown below.

The vertical axis states the correction deviation aka dev in degrees west or east, where east is again positive.

The horizontal axis states the ship's heading cc in degrees divided by ten. Thus, when steering a compass course of 220°, the deviation will be 4° W.

As the primary navigation instrument for the helmsperson this type of compass will be in a fixed position, which means we can create and implement a deviation table. Since magnetic deviation is a factor the conversions between true courses and compass courses are done via tc = cc +var + dev.

Remember to assign (−) for west and (+) for east compass errors.

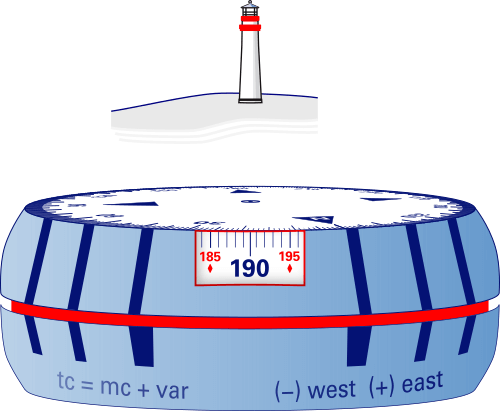

The illustration shows us that we are sailing a compass course of 12°C.

A correction for deviation isn't possible for such compasses since these are not used in a fixed position.

Here we take a bearing of a lighthouse by holding a puck-shaped bearing compass with an infinity prism at eye level and read down the line of sight: 190°M.

Although the tc = mc + var is arguably more stringent, tc = cc + var is also widely used: if deviation is irrelevant, then mc and cc produce the same course.

Note, that on most modern sailing yachts the deviation will be less than ±3°.

When a steering compass, see figure 3.5, is newly installed it often shows larger deviations than this and will require compensation by carefully placing small magnets around the compass. It is the remaining error that is shown in your deviation table.

You should check the table every so often by placing the yacht in the line of a pair of leading lightsleading lights and turning her 360 degrees, a time-honoured method known as “swinging the compass”.

Conversely, a hand bearing compass, as illustrated in figure 3.6, does not have a deviation table, and crucially bearings should be taken as far from metal and electrical wiring as possible.

tc = cc + var as well as tc = mc + var are both suitable.

Phrases such as “conversions between tc and cc or mc” or “correct and uncorrect true courses” are interchangeable.

Correcting for both deviation and variation

To convert a compass course into a true course, we can still use our equation but we need to add the correction for deviation:

cc + var + dev = tc

- Example 1: we sail a compass course of 330°, with a corresponding deviation of +3°, see table, and from the nautical chart we find that at our location the variation is +3°;

330° cc + 3° var + 3° dev = ?° tc

giving a true course of 336° which we can plot on the chart. - Example 2: we change our compass course to 220°, the deviation is −4° (table) and the variation is still +3° (chart);

220° cc + 3° var + −4° dev = ?° tc

giving a true course of 219°. - Example 3: after sailing extensively our compass course is still 220°, therefore the deviation is still −4° (table), but since we are at a new location the nautical chart specifies a variation of −10°;

220° cc + −10° var + −4° dev = ?° tc

giving a true course of 206°.

Converting a true course into a compass course – finding a Course to Steer (CTS) – is a little less straight forward, but it is still done with the same equation.

- Example 4: the true course drawn on the chart is 305° and the local variation is +3° (found in the nautical chart), yet we don't know the deviation;

?° cc + 3° var + ?° dev = 305° tc

Luckily, we can rewrite this so this reads:

cc + dev = 305° tc − + 3° var = 302°

In plain English: the difference between the true course and the variation (305 − + 3) = 302 should also be the summation of the compass course and the deviation. So, we can tell our helms person to steer 300°, since with a cc of 300° we have a deviation of +2°,as can be deduced from the deviation table. - Example 5: the true course from the chart is 150° and we have a western variation of 7 degrees (−7°). We will use the rewritten equation to get:

150° tc − − 7° var = cc + dev = 157°

From the deviation table we find a compass course of 160° with a deviation of −3°.

Voilà!

Lateron in this course we will discuss how to compensate for leeway and find CTScompensate for leeway and find CTS and to compensate for tidal streams and find CTScompensate for tidal streams and find CTS.

Magnetic course

The magnetic course (mc) is the course after magnetic variation has been considered, but without compensation for magnetic deviation. This means that we are dealing with the rewritten equation from above:

tc − var = cc + dev = mc.

Magnetic courses are used for three reasons:

Figure 3.7 –

Three types of north:

True, Magnetic, Compass.

- To convert a true course into a compass course like we saw in the last section.

- On vessels with more than one steering compass, also more deviation tables are in use; hence only a magnetic or true course is plotted on the chart.

- Bearings taken with a hand bearing compass often don't require a correction for deviation, and are therefore useful to plot on the chart as magnetic courses.

Note, that the actual course lines the navigator draws (plots) on the chart are always true courses, unless labeled as mc or cc.

In chapter 4chapter 4

we will be plotting courses on the chart.

To summarise, we have three types of “north” (true, magnetic and compass north), correspondingly we have three types of courses: tc, mc and cc. All these are related by deviation and variation.

Compass errors • Breton Plotter

Brilliantly, a Breton PlotterBreton Plotter makes it possible to work with magnetic courses.

Looking back to the example in Figure 2.10Figure 2.10 we find a true course of 080° in the direction from the wind turbine to the super buoy.

From the inner card of the compass rose in the chart we get a variation of +12 for 2024.

Instead of reading off the scale at the 0, we read off the scale at 12° E, which gives us a magnetic course of 068°M.

In the same way we could include deviation and thus acquire a compass course.

Glossary

- Variation: the angle between the magnetic north pole and the geographic north pole. Also called the magnetic declination. Note that magnetic inclination is the angle between the magnetic field and the horizontal plane. At the poles the field dips into the earth. Therefore, a corrected compass can generallly only function in one hemisphere.

- Secular variation: the change of magnetic declination in time with respect to both strength and direction of the earth's magnetic field; view these declination / variation maps with isogonic lines:

world – interactive and historical declination and an

animated-in-time GIF.

“Isogonic declination” is defined as lines of equal declination, and keep in mind that declination is exchangeable with variation. - West “ − ”, east “ + ”: west variations / declinations as well as west deviations are designated with a negative sign by convention due to the compass card's clockwise ↻ direction.

- Deviation: the compass error caused by electrical currents and / or metal objects.

- Deviation table: a table containing deviations in degrees versus the ship's heading (compass course) in degrees; usually plotted in a graph / card.

- True course: the course corrected for compass errors and plotted on the chart, tc and is equal to Course over Ground (COG) or Course Made Good (CMG). Note that COG is an instantenous value, whereas CMG is the combined net course after some period of time and maybe several course changes.

- Compass course: (cc) the course which is corrected for both variation and deviation.

- Magnetic course: (mc) the course which is only corrected for variation.

- cc + var + dev = tc: this equation shows the connection between the compass course, its errors and the true course. It can also be read as: tc − var = cc + dev.

See the next chapter…

- Course overview: goals and introduction

- Positions: latitude, longitude, nautical mile, scale, knots

- Nautical chart: coordinates, positions, courses, chart symbols, projections

- Compass: variation, deviation, true • magnetic • compass courses

- Plotting and piloting: LOPs, (running) fix, dead reckoning, leeway, CTS, CTW, COG

- Advanced piloting: double angle on the bow • four point • special angle fix, distance of horizon, dipping range, vertical sextant angle, radians, estimation of distances

- Astronomical origin of tides: diurnal, semi-diurnal, sysygy, spring, neap, axial tilt Earth, apsidal • nodal precession, declination Moon and Sun, elliptical orbits, lunar nodes

- Tides: tidal height prediction, chart datums, tidal curves, secondary ports

- Tidal streams and currents: diamonds, Course to Steer, Estimated Position

- Aids to navigation: buoys, leading lights, ranges, characteristics, visibility

- Lights and shapes: vessels sailing, anchoring, towing, fishing, NUC, RAM, dredging

Also you can download the exercises + answers PDF ![]()