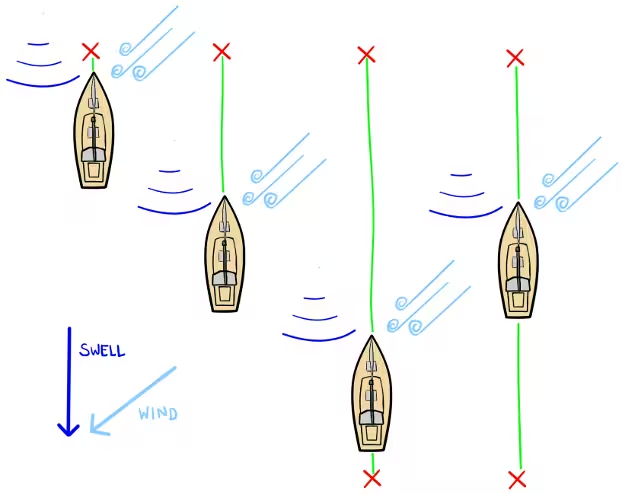

Using the second anchor

Taking a line ashore

The stern anchor or a line to a rock / beach allows you to point the yacht into the swell, instead of upwind.

This is also a common technique in Greece and Turkey for two further reasons:

- it transforms deep bays – the “Vathy” toponym is aplenty – into proper anchorages by dropping the bow anchor close to the shore.

- it provides safety in popular anchorages (at least in the main yacht charter season) where swinging at anchor isn't an option.

First place the main anchor by using the engine.

Secondly bring the stern anchor into play, ideally with the dinghy. If there is a beach or suitable rock, place the secondary anchor there.

In Turkey this manoeuver is called “gulet method” named after the traditional fishing vessels, the gulet motorsailers, but it is better known as “long-line-ashore mooring”; more insights here…

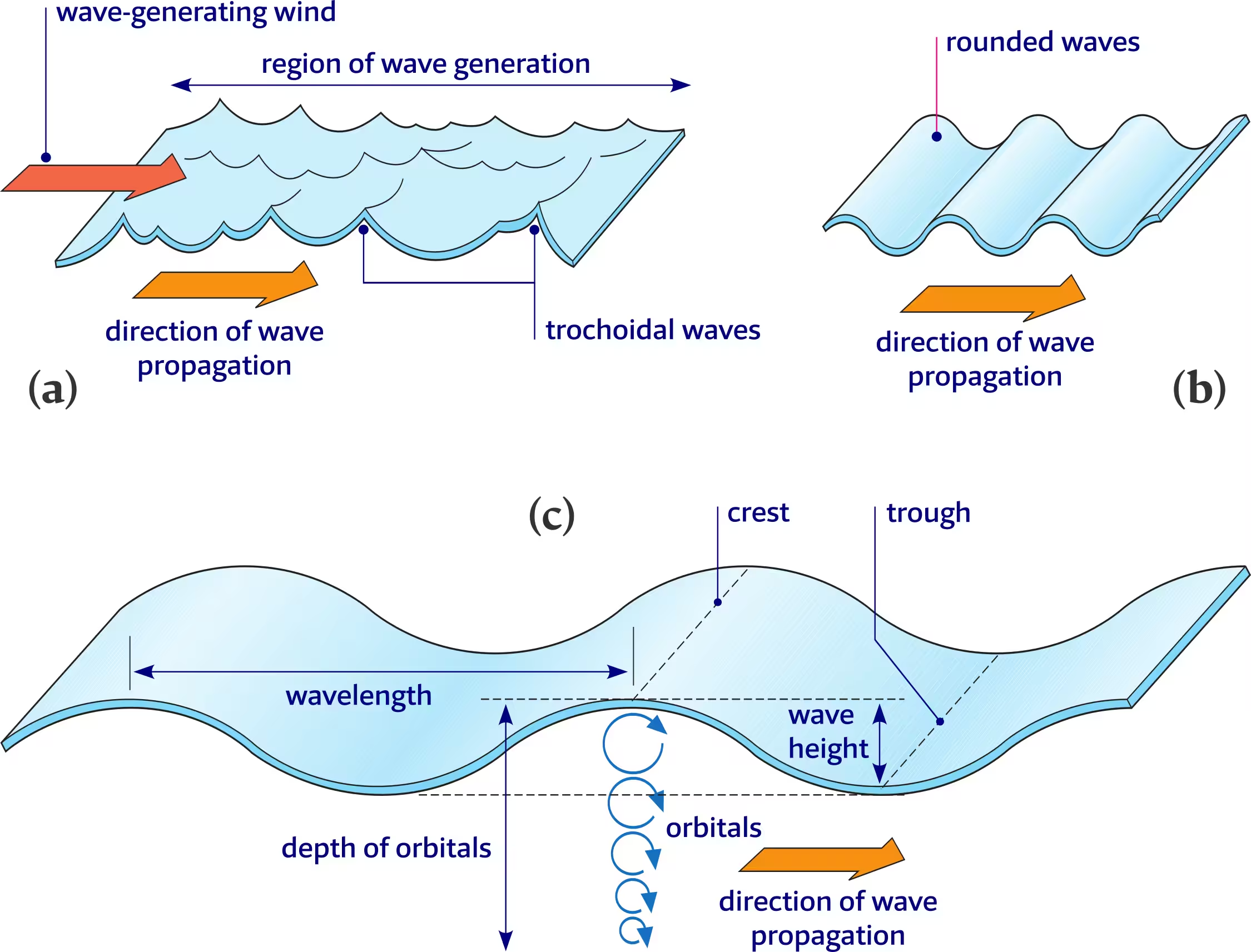

Wind generated waves

Most ocean waves are generated by wind and are described by crest and trough, fetch, wavelength and waveheight, trochoidal or swell (rounded waves) and the orbitals below.

With a wind blowing at a constant speed in the same direction, the size of the wave it generates is a function of its speed, and the extent of open ocean that it affects is known as the fetch.

Seas and swells

At sea, winds rarely blow at a constant speed in the same direction for very long. As a result, where wind-generated waves are forming there is often a jumbled mix of waves of different heights, wavelengths, and directions. This is known as a sea. Waves in a sea are often trochoidal (with pointed crests and rounded troughs), see trochoid, from Ancient Greek τροχός trochos “wheel”.

As waves travel away from an area of wave-generation they may sort themselves so that waves of similar height and wavelength are traveling in the same direction. Here, the waves are smoother and more rounded. This is known as a swell.

(a) Seas – trochoidal waves

(b) Swells – rounded waves

(c) Movement in a wave – orbitals

Movement in a wave

Wind-driven waves in deep water transfer energy and form horizontally, but cause little net movement of water.

An object on the surface caught by a wave tends to roll, turn in a circle, and return to its starting point. It is not swept along with the passing wave.

Such waves generate orbital motions in the top layer of the water column.

The orbitals gradually diminish in size and disappear at a depth of about half the wave’s wavelength.

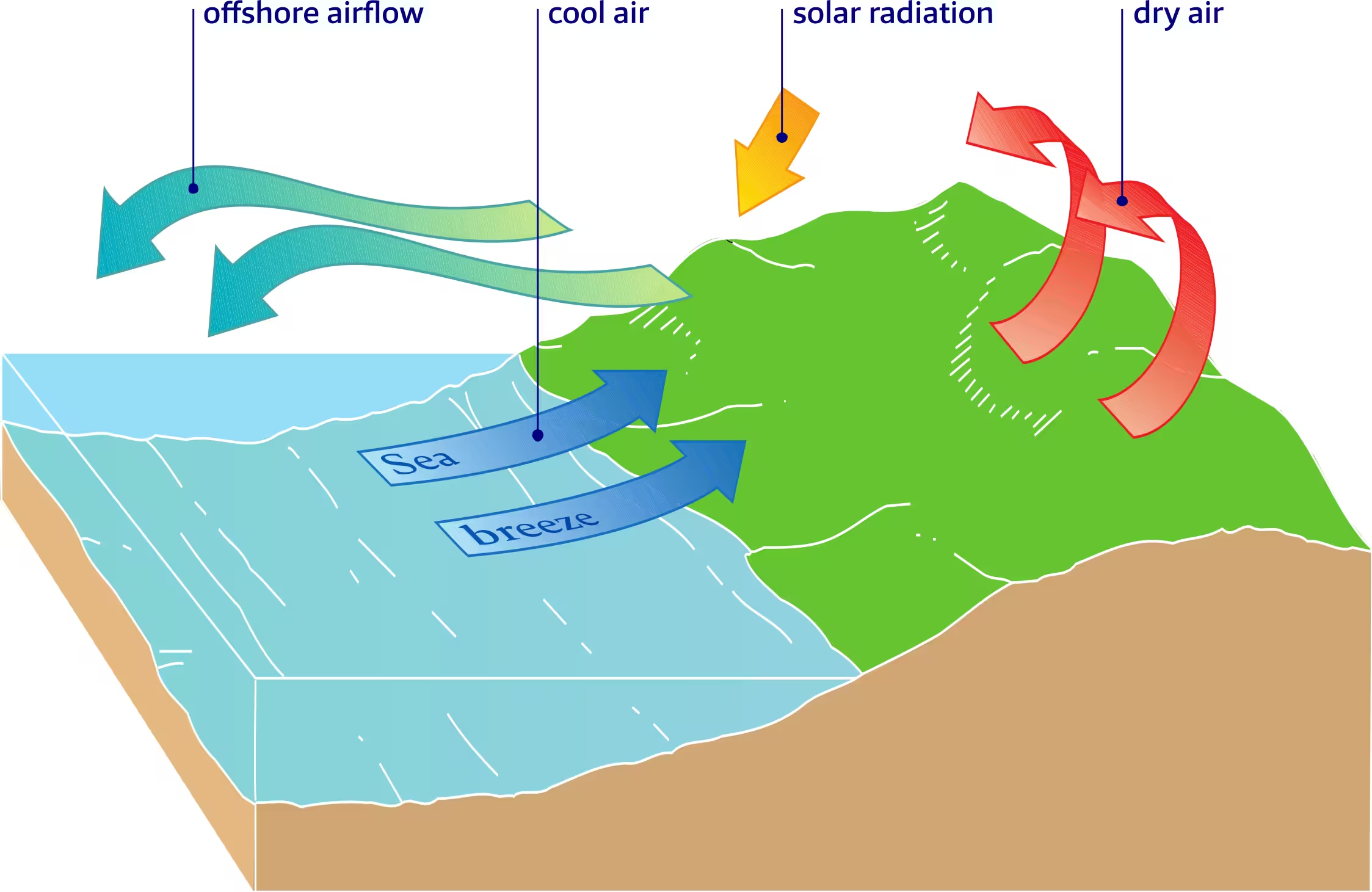

Night and day

Typically when sailing in an archipelago such as in Greece, during the anchoring manoeuver the day wind might blow into the anchorage from the open sea, while the night wind might well blow from the opposite direction (from the beach towards the sea).

Use the dinghy to place the stern anchor towards the beach or actually on the beach.

Mind the possibility of shafing: a great tip from this logbook.

Obviously, the same set-up is appropriate to deal with true sea breeze & land breeze transitions as well.

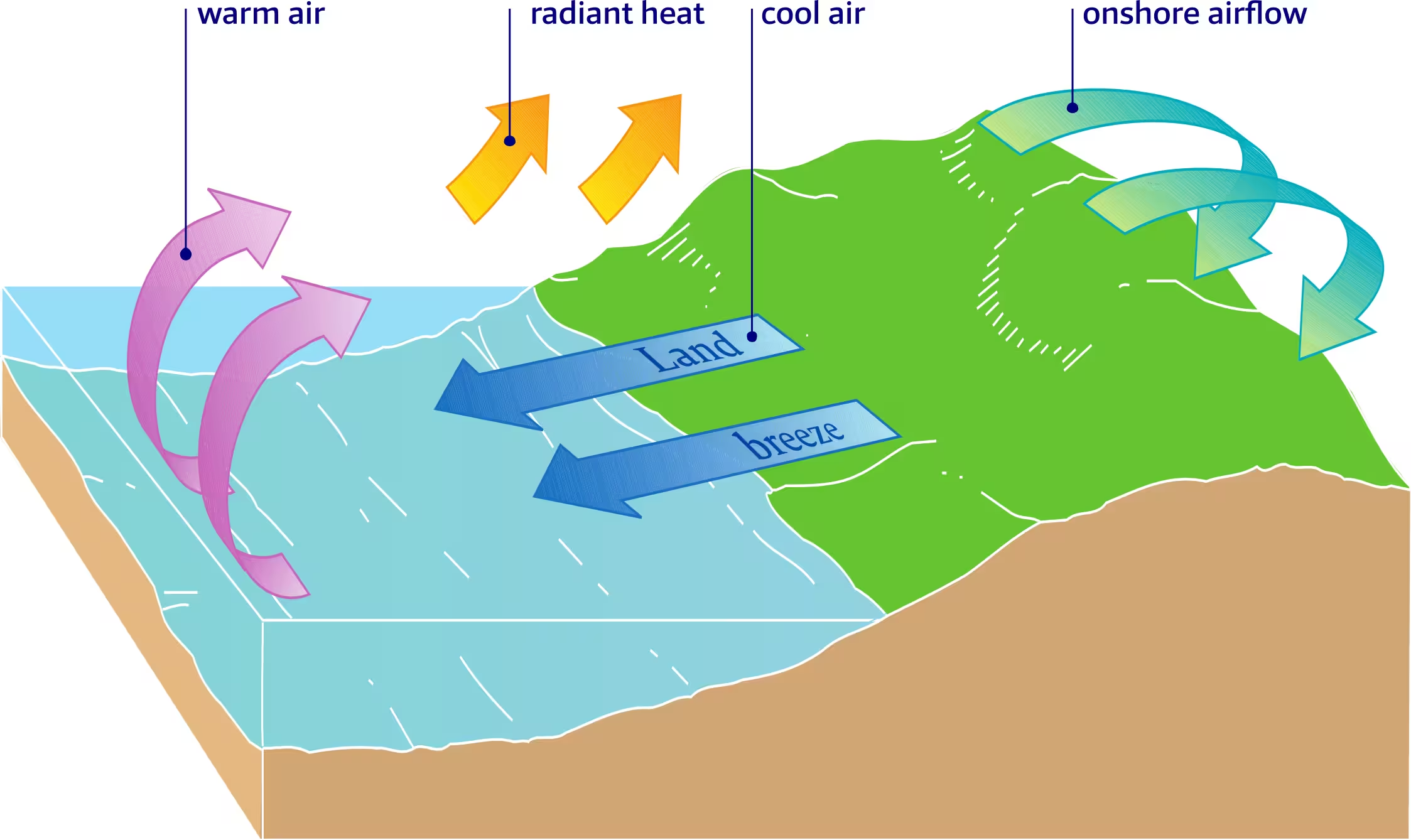

Coastal breezes

Seawater has a higher heat capacity than land. Given the same conditions of solar irradiation, seawater both gains and loses heat energy more slowly than adjacent land. This difference in thermal characteristics gives rise to coastal breezes that change direction during a 24-hour period.

Coastal breezes vary markedly in intensity and regularity, depending on the location and time of year. They are most pronounced in the tropics and subtropics, and in temperate latitudes during the summer.

Sea breeze

- On a bright sunny day the land warms more quickly than the nearby surface water of the sea.

- Solar radiation is absorbed by both sea and land, but the heat capacity of the land is less and it warms up more quickly.

- Dry air close to the land surface warms quickly and rises.

- Cool, moist air close to the sea surface moves ashore to replace the rising air. A cool onshore sea breeze is thus generated during the day.

- Aloft, an offshore airflow descends to complete the cycle.

Land breeze

- At night, the land cools faster than the nearby ocean surface.

- Radiant heat energy is lost more rapidly from the land than from the sea.

- Warm moist air close to the ocean surface rises.

- Cool air from the land moves offshore to replace the rising air. A cool offshore land breeze is generated at night.

- Aloft an onshore airflow descends to complete the cycle.

Handling swell

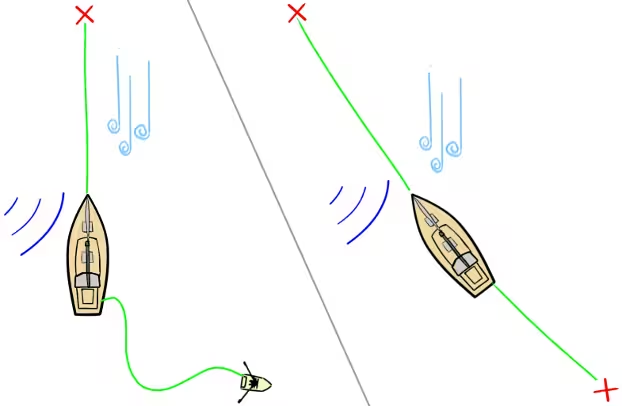

Rolling (or other motions) – often due to swell – is one of the bigger discomforts on an anchored yacht.

The image above illustrates that by placing the second anchor not directly downwind, you can point the nose into the swell (or other waves). This will result in a more comfortable behaving yacht, see ship motions: heave, sway, surge, pitch, yaw and roll.

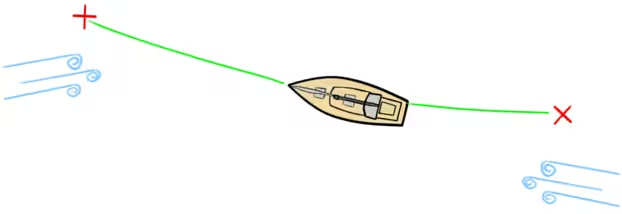

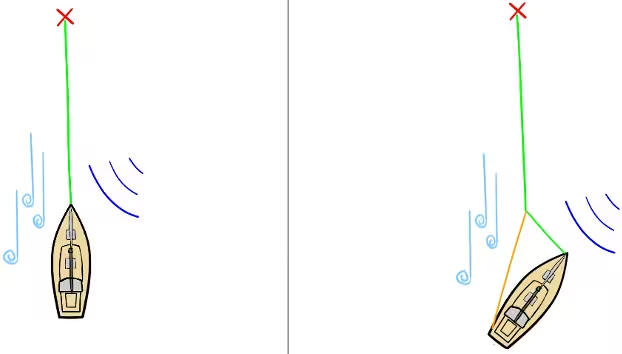

Rigging a bridle

If placing a second anchor or the “long-line-ashore method” isn't possible, you can “rig a bridle” – even if the wind direction fluctuates – as shown in the image below.

- Connect a line to the anchor chain either with an anchor hook or a rolling hitch. Add one or two extra turns before the hitch to make it extra resistant to slipping. The rolling hitch is simple and quick, and can be untied even after it has been loaded.

- Let out several metres of chain.

- Tighten the line on a cockpit winch to create the bridle, and if necessary adjust in wind shifts.

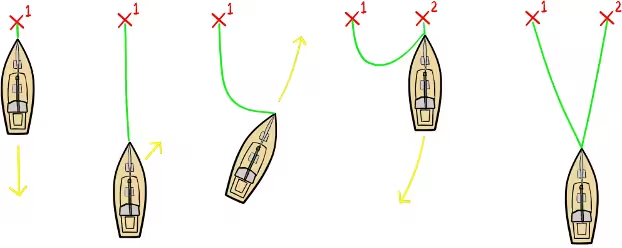

Two anchors to reduce yawing

In shifty wind conditions – which invariably causes the boat to “yaw at anchor” – it is helpful to deploy both anchors from the bow.

Note that yawing at anchor refers to a vessel swinging back and forth around its anchor point. This motion can reduce the effectiveness of the anchor and increase the load on the rode, potentially leading to dragging.

To counteract this motion you can place the anchors at 20° – 35° to either side of the bow, and as always: the longer the chain, the better the scope.

Don't overcomplicate things: in stormy weather or dangerous situations deploying a second anchor is the opposite of KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid). If one anchor drags it will be more dangerous getting out of the anchorage; e.g. the line of the stern anchor might foul the propellor.

- Anchoring course

- Seabed – where to anchor

- Anchors & anchor parts

- Anchoring techniques

- Second anchor

- Mediterranean mooring

- Anchoring tips & glossary

Further reading

Etesian, Meltemi wind

Ionian & Aegean combined

Avoid the databases: last-minute sailing holidays

Carian coast, Turkey

Athens yacht charters guide